Reconsidering the memoir with a 13,000-year-old fossil

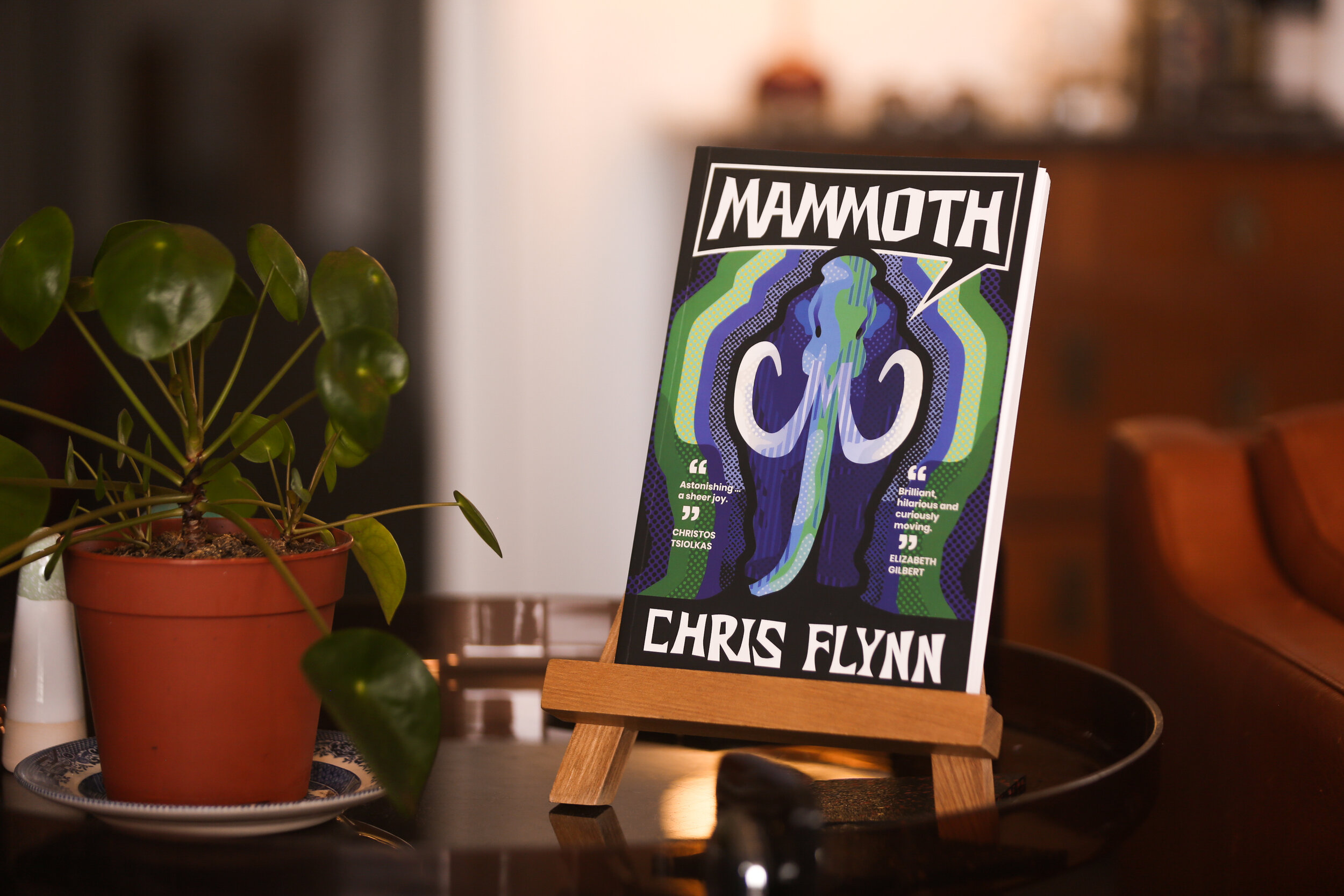

/Author Chris Flynn gives old bones a new voice in Mammoth

Chris Flynn. Photo by Georgia Butterfield.

Difficult accents, (very) unreliable narrators, dark humour and shifting perspectives abound in Chris Flynn’s first novel, A Tiger in Eden (2012, shortlisted for the Commonwealth Book Prize), and The Glass Kingdom (2014). Both were contemporary, evocative tales of men escaping — and trapped — by their past experiences with violence.

Those elements also feature in Flynn’s latest novel, Mammoth, an account of history and climate change as told by a 13,000-year-old fossil awaiting the sale of his remains. But this whimsical take on what Salvador Dali called ‘the persistence of memory’ has brought him some new fans — teens and history buffs.

“I have never written a book for younger readers,” Flynn admits on a call from his home on Phillip Island, Victoria, just off Australia’s southern coast. “I do wonder if perhaps the book might find a bit of a younger audience unexpectedly as it does present history in quite an appealing and fun way. And, you know, as we all know, when you’re taught history in school, it can be pretty dry and boring and hard to get into. So although it's not necessarily all factual, if it's a nice introduction to something that the kids are not interested in normally, then that can’t be a bad thing.”

The author’s own introduction to palaeontology, American history and telepathically communicating dinosaur fossils began six years ago when Flynn connected the dots between a curious news event and bone collecting in the early 1800’s. He first came across an account of a March 2007 natural history auction in New York that attracted famous buyers such as Nicolas Cage and Leonardo DiCaprio and later resulted in the repatriation of smuggled fossils back to Mongolia. Then, he had heard stories about US Founding Father Thomas Jefferson’s obsession with mammoths and how he thought that if fossils could be found on American soil, it would prove to Europe that US democracy was built on land where giants once roamed.

“When I heard about the 1800 stuff, I thought, ‘Oh, there's a bit of a link here,’” Flynn explains. “These men of power and influencers are still commodifying these bones for their own purposes to try and show everyone how macho they are. But then when I thought, ‘OK, there's a good story here to be told. Maybe the creatures at the auction could tell us how and why they wind up there?’ It was instantly a massive story.”

How to tell it would emerge through extensive research, not just to make sure he got the details right, but to make sure he got those accents, those narrators, that humour and those perspectives right. In particular, Flynn couldn’t help but read historical findings in the voice of a pompous, rich 19th Century gentleman-scientist, which transformed into main protagonist Mammut.

“It was kind of like the whole time, this huge mammoth creature was sort of standing behind me watching me, waiting patiently for me to get started,” he says. “Then one day, out of the blue really, a totally inauspicious moment. It was a Tuesday afternoon at 4 pm or something. I just started writing it and the voice of the mammoth was really strong and powerful and clear for me.”

Chris’s latest novel is also available as an audiobook. Photo by Georgia Butterfield.

Then it was just a joy for Flynn to create the rules of this world, determining that the time in which a fossil was found would become its conscious age of “speaking.” Thus Mammut, unearthed in 1801, has an expansive 220-year knowledge of human history, while a 67-million-year-old Tyrannosaurus bataar fossil comes across as an immature youngster, dug up as he was in 1991 and “living” in a Florida warehouse.

T. Bataar speaks “a little bit like Keanu Reeves from Bill and Ted’s Excellent Adventure,” Flynn says with a laugh. “So it was loads of fun assigning the voices according to where they spent time as fossils.”

Adding another dimension to the project was having Mammoth as an audiobook, read by actor Rupert Degas. “He’s this iconic voice actor who has done a million movies and he did every single voice,” Flynn marvels. “When I was sent the audio samples, I couldn't believe it. I thought, ‘That cannot be the same guy who's doing the mammoth, and the penguin from Boston, and the tyrannosaur from Miami. It can't be, but it is!”

“Let me tell you what I wish I’d known/When I was young and dreamed of glory

You have no control/Who lives, who dies, who tells your story”

– Washington and Company (“History Has Its Eyes On You,” Hamilton)

All of those voices touch on a bigger conceit for Flynn. “I’m fascinated with this idea of memory and how we remember things, the stories that we tell, and how, I think, it's a very human thing to reinvent our own memories for our own purposes,” Flynn says. Although he concedes his own memory is “terrible,” he adds, “I’m convinced people re-write their own memories to suit their current narrative.”

With Mammut, “I love that he is basically telling this story verbatim as if it's absolutely what happened, but he is embellishing, too, because he's also a storyteller,” Flynn says. “I didn't want him to get away with that easily. So I wanted the other creatures to pull him up on that and say, ‘Wait a minute, you weren't even there when that happened.’ And then he has to come up with some excuses as to why he knows that particular element of the story.”

Yet by telling human history along with his own, Mammut charts a path for his—and our—future. “He has grown to an understanding that some of us are not that different from him or the struggles that he faced,” Flynn says. “A lot of humans also face those struggles of disenfranchisement, loss of environment, people not treating you as equal.” These parallels between the lived experiences of extinct species and the current trials of humanity are indeed intentional. “We do have that tendency to elevate ourselves above nature when really, we're just one single element of the ecosystem, but we're a pretty aggressive one,” Flynn adds.

“I guess one of the messages from the book is this idea that the more integral in the holistic approach to the natural world and our place in it,” he says, “that would be a little bit healthier for all parties involved.”

Mammoth by Chris Flynn (UQP) is available in paperback and as an audiobook.